S creenwriters have a tendency of defining the three act structure by either vehemently opposing it or swearing by it. Some define it entirely differently than others. How is that possible? Well, let’s answer ‘what is the three act structure,’ learn its original intention, and see if we can find some middle ground between the many perspectives.

Subscribe for more filmmaking videos like this.

A three-act structure keeps your beginning separate from your middle and your middle separate from your end. That’s it.

Thanks to some entrepreneurial screenwriters, formulas have been built on top of this basic outline via screenwriting manual after screenwriting manual. But before we get into the intricacies of story structure, let’s provide an all-encompassing three act structure definition.

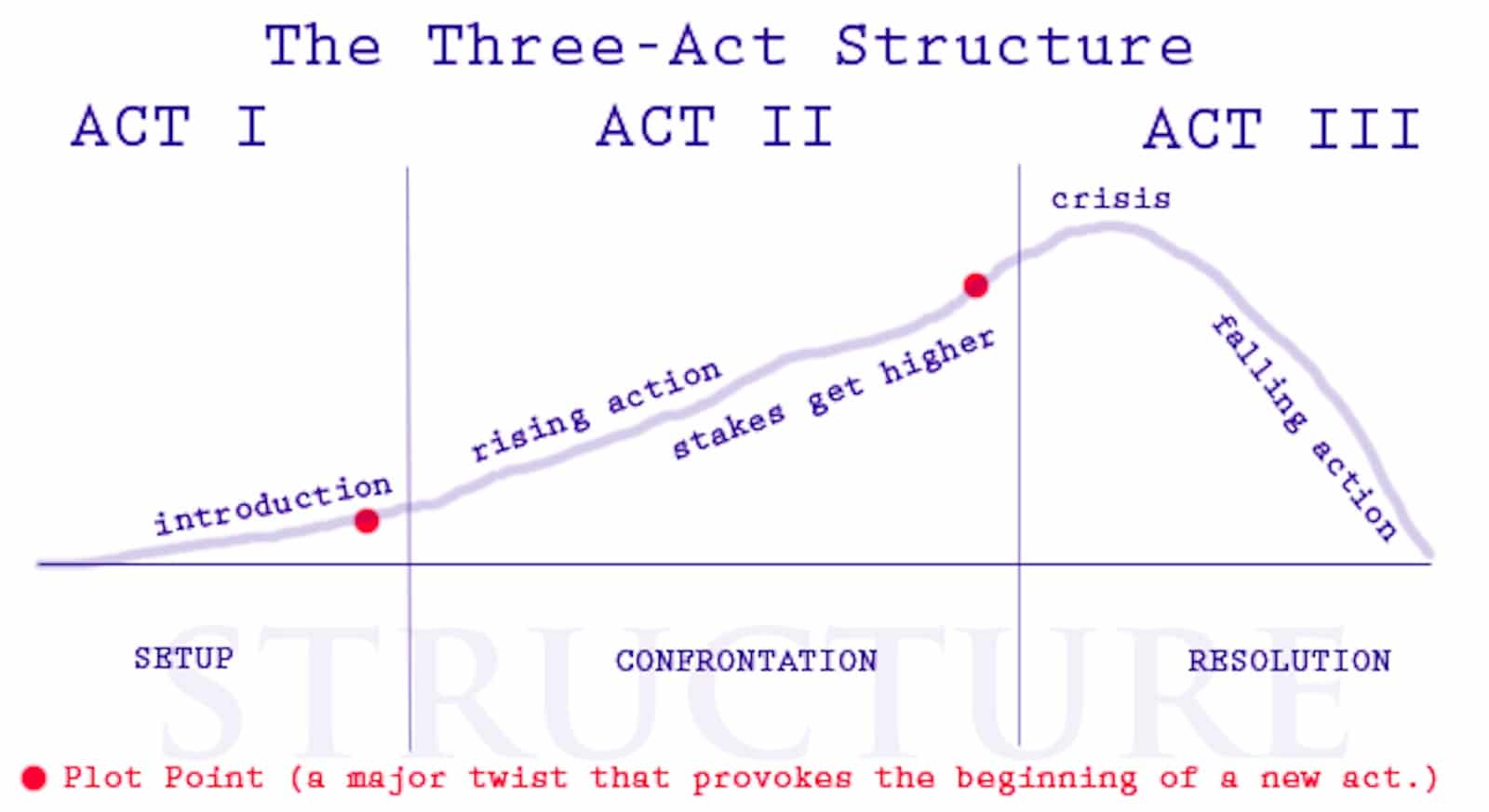

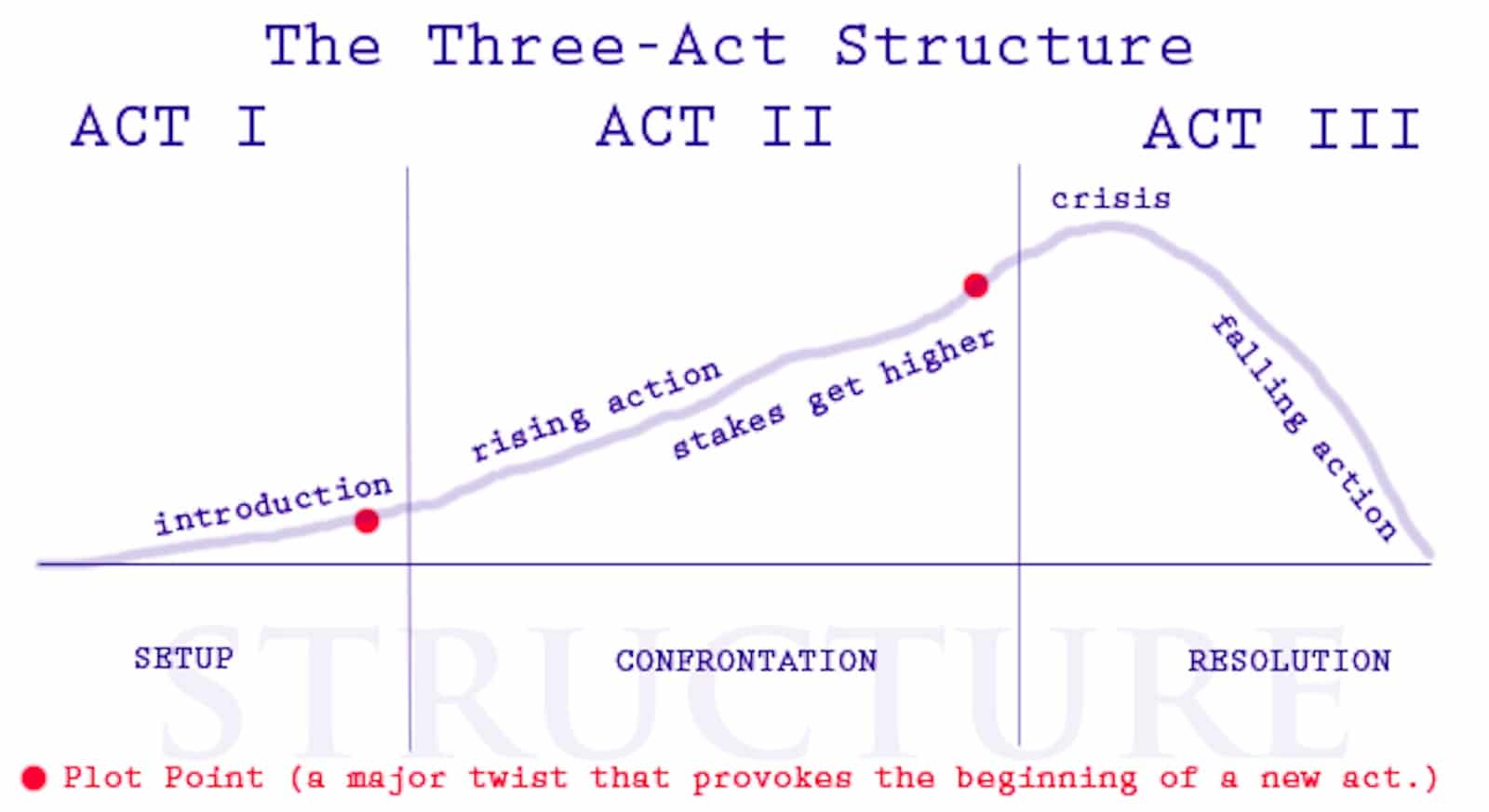

The three act structure is a narrative model that divides stories into three parts — Act One, Act Two, and Act Three, or rather, a beginning, middle, and end. Screenwriter Syd Field made this ancient storytelling tool unique for screenwriters in 1978 with the publishing of his book, Screenplay. He labels these acts the Setup, Confrontation, and Resolution.

Some writers label these three acts the setup, build, and payoff. Both are correct. But the basic point of each of these acts is that they have their own set of guidelines to develop, build, and resolve a story.

On a basic level, Act One sets up the world, characters, the character’s goal, as well as the conflicts or obstacles that are preventing them from achieving their goal. Act Two raises the stakes for the character to achieve the goal, escalating the conflict. Act Three resolves the story with either an achievement of that goal or a failure.

Now that we've defined the three act structure in film, I want to rewind to the early days of storytelling. No, not Syd Field.

Aristotle’s Poetics is the first book any aspiring screenwriter should read. It’s the first playwriting manual on record.

But that’s not why you should read it.

The theoretical text lays out critical insights into the foundations of all of storytelling. All stories (or using his language, tragedies and comedies) must have a beginning, middle, and an end. These represent the three acts in the three act structure.

This is important to note before we define what the three act structure is considered to be today. Some screenwriters get much more detailed with the requirements of what goes into each of these acts.

But the most important takeaway of the 3 act is understanding that one event must lead to another and then to another — this unifies actions and meaning and creates the semblance of a story.

A beginning, middle, and an end, isn’t a formula. It brings cohesion to otherwise random events. It’s what makes a story, a story.

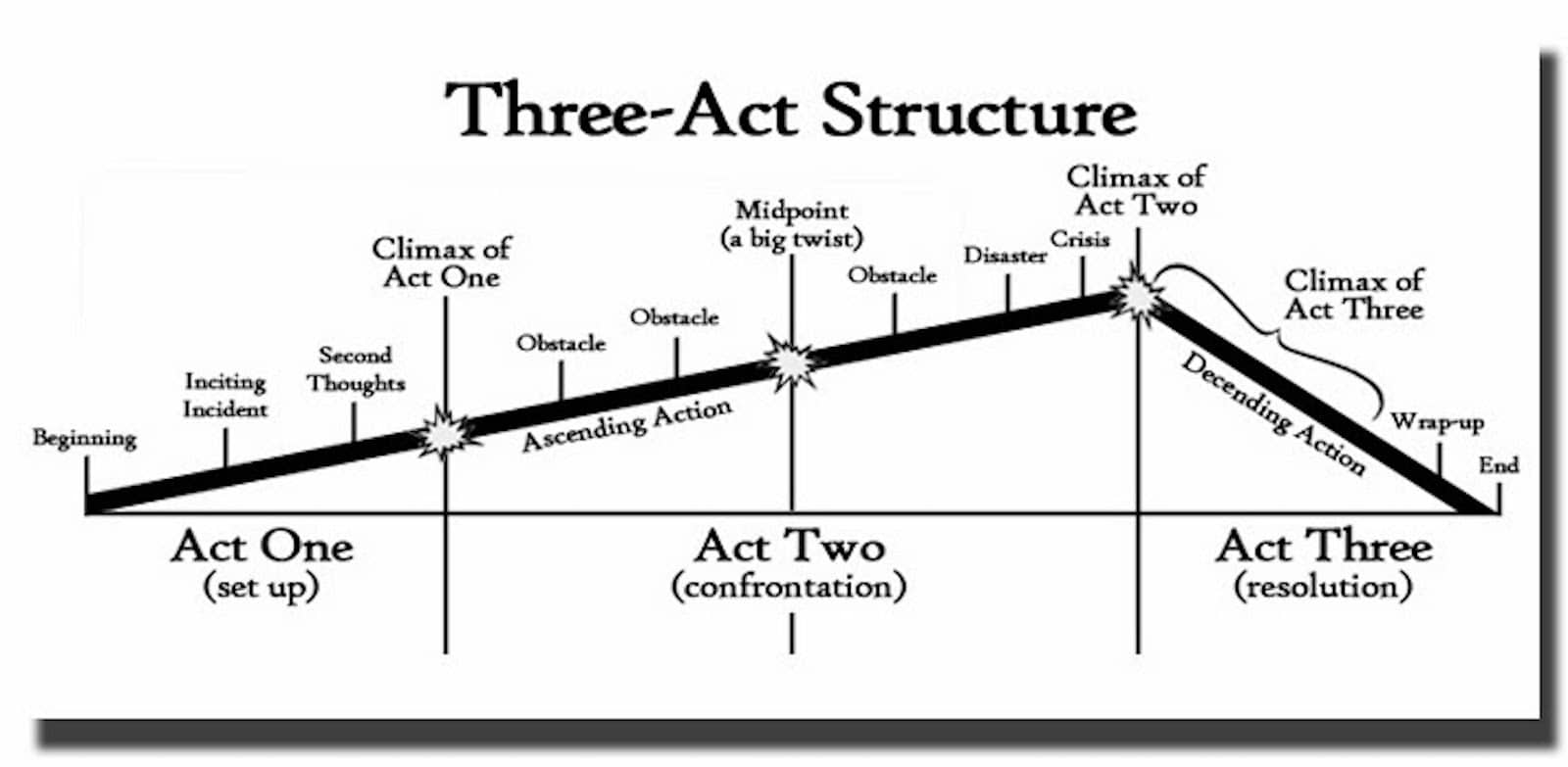

Today, when writers discuss three act structure, this is the model they’re typically referring to:

This is pretty standard. We’ll go over each act below, but this should be used as a guideline, not a rule book.

The setup involves introduction of the characters, their story world, and some kind of ‘’inciting incident,” typically a moment that kickstarts the story. It’s usually the first 20-30 minutes of a film.

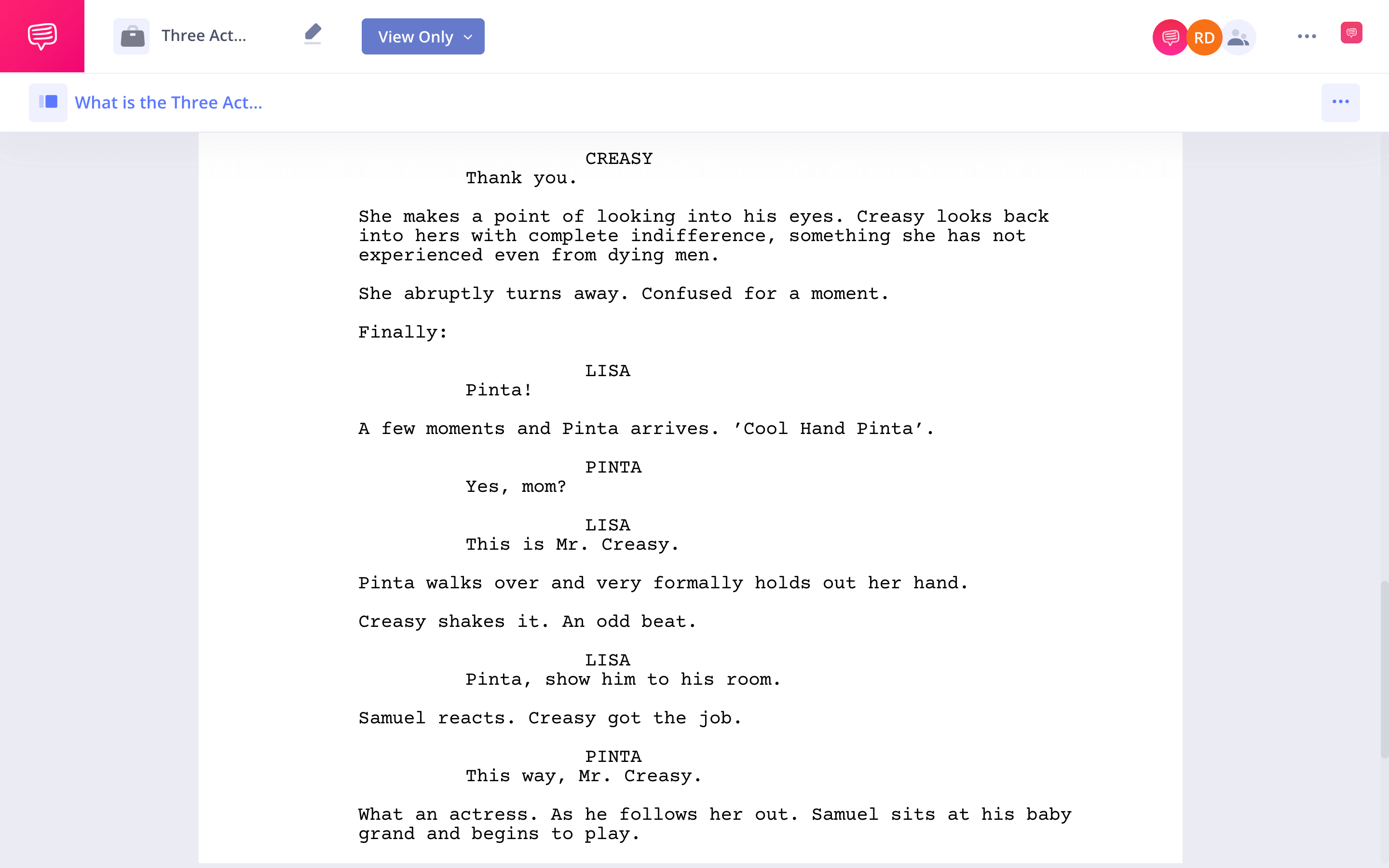

Let’s take a look at the inciting incident in Man on Fire’s screenplay, which we imported into StudioBinder’s screenwriting software:

The inciting incident here is Creasy’s introduction to Pinta, the girl for whom he’ll be a bodyguard. It’s an inciting incident for two reasons. First, it begins the key relationship that propels the movie: the down-and-out Creasy finds a reason to live in Pinta. Second, it starts the core narrative arc: Creasy gets the job and his duties as a bodyguard who will stop at nothing to protect Pinta begins.

This inciting incident happens on page 16, a little deeper into the script than most inciting incidents, but it’s a bit of a longer script, so it fits with the pacing.

Typically a first act ends around 20-30 pages into a screenplay, at around the 25% mark.

The middle of your story should raise the stakes, you want the audience to keep watching. This is the main chunk of the story and often leads us to the worst possible thing that can happen to the character.

Note that the plot doesn’t have to move in one direction. There are ups, downs, turnarounds. In fact, if the story just builds and builds in a straightforward manner, you may bore the audience with a predictable movie.

The end should bring some kind of catharsis or resolution, (regardless if the ending is happy or sad). It’s a sigh, either of relief or despair.

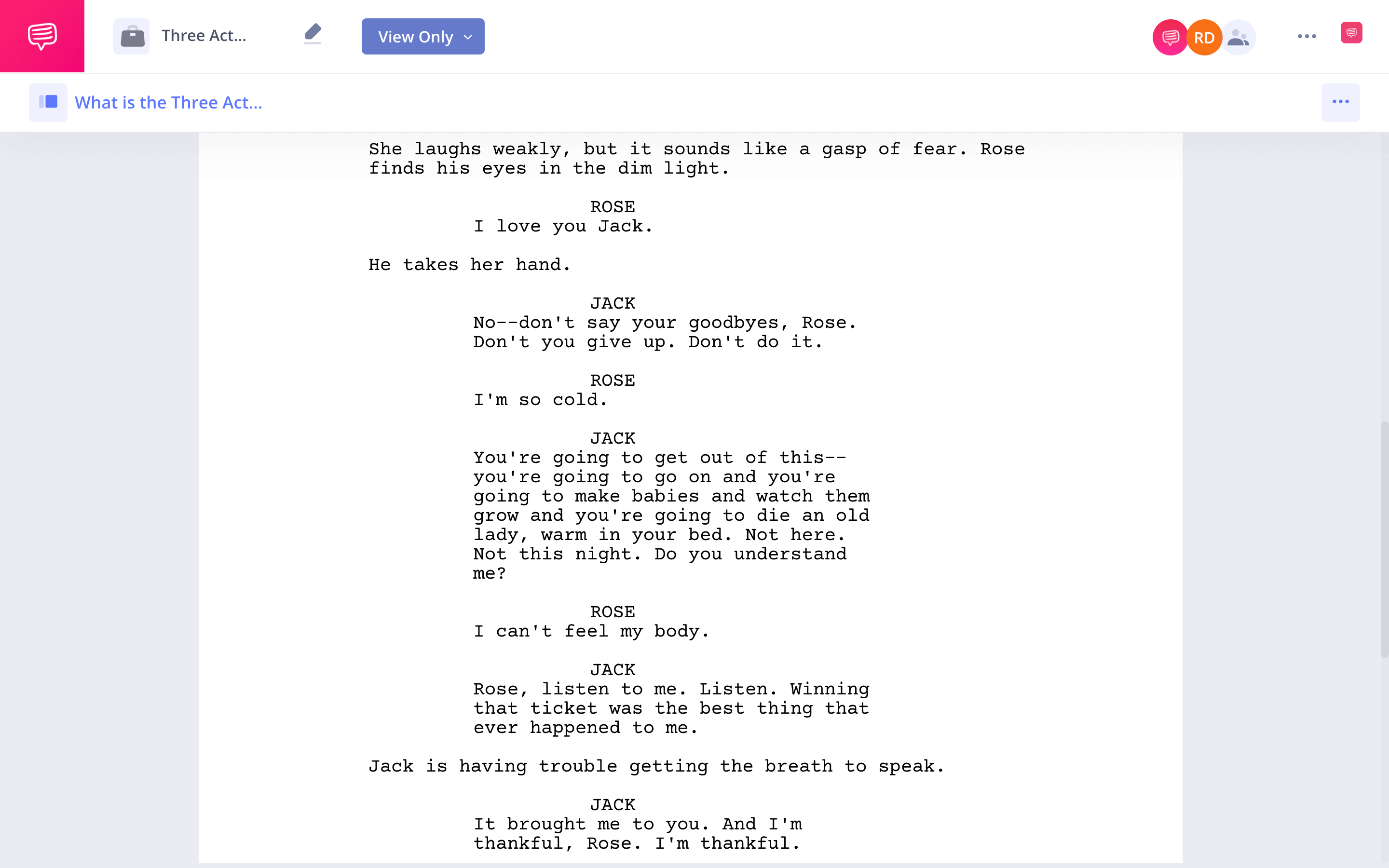

Titanic has one of the most famous climaxes of all time– check it out on the page:

Titanic is a tragedy in all the best ways, and this scene highlights why it’s so successful. The audience is devastated, yes, but there’s still the sentiment that it’s better to have loved and lost than to have never loved at all. It’s bittersweet, heartwarming and tear-jerking.

As you may have noticed, each act has their own set of guidelines that help develop, build, and resolve a story. What exactly these guidelines look like depends on the structure you want to subscribe to (if you want to subscribe to any at all).

Here’s one option:

This one looks a bit more involved, doesn't it?

Do I really need two obstacles halfway through the second act? Will my story suffer with three or five, or one?

Of course not. You also can have as many of these “plot points” as you need to, to tell an effective, meaningful story.

One such structure that can help make sense of a traditional 3-act structure was developed by Blake Snyder and it's called Save the Cat! Snyder's Save the Cat! structure takes a traditional 3-act structure and breaks it up into 15 story beats.

Watch as we take this beat sheet and run Avengers: Infinity War through to see how they gave Thanos a complete protagonist character arc.

There is no predetermined formula for knowing exactly where and when these critical events should occur within each act.

Most of the time, big events like the inciting incident or resolution will obviously, and naturally, happen in their intended acts, but the specifics should come from the organic nature of your story, not a formulaic page count or act break.

Now, let’s take an in-depth look at the three act structure in action.

Most mainstream Hollywood films follow a conventional three act structure. Once you start paying attention, you’ll notice that a lot of the story beats they hit happen in nearly identical places.

Writer and story expert K.M. Weiland has synthesized these recurring story beats into a three act structure that is subdivided into eight sections. Of course, following this structure doesn’t necessarily mean a movie is unoriginal.

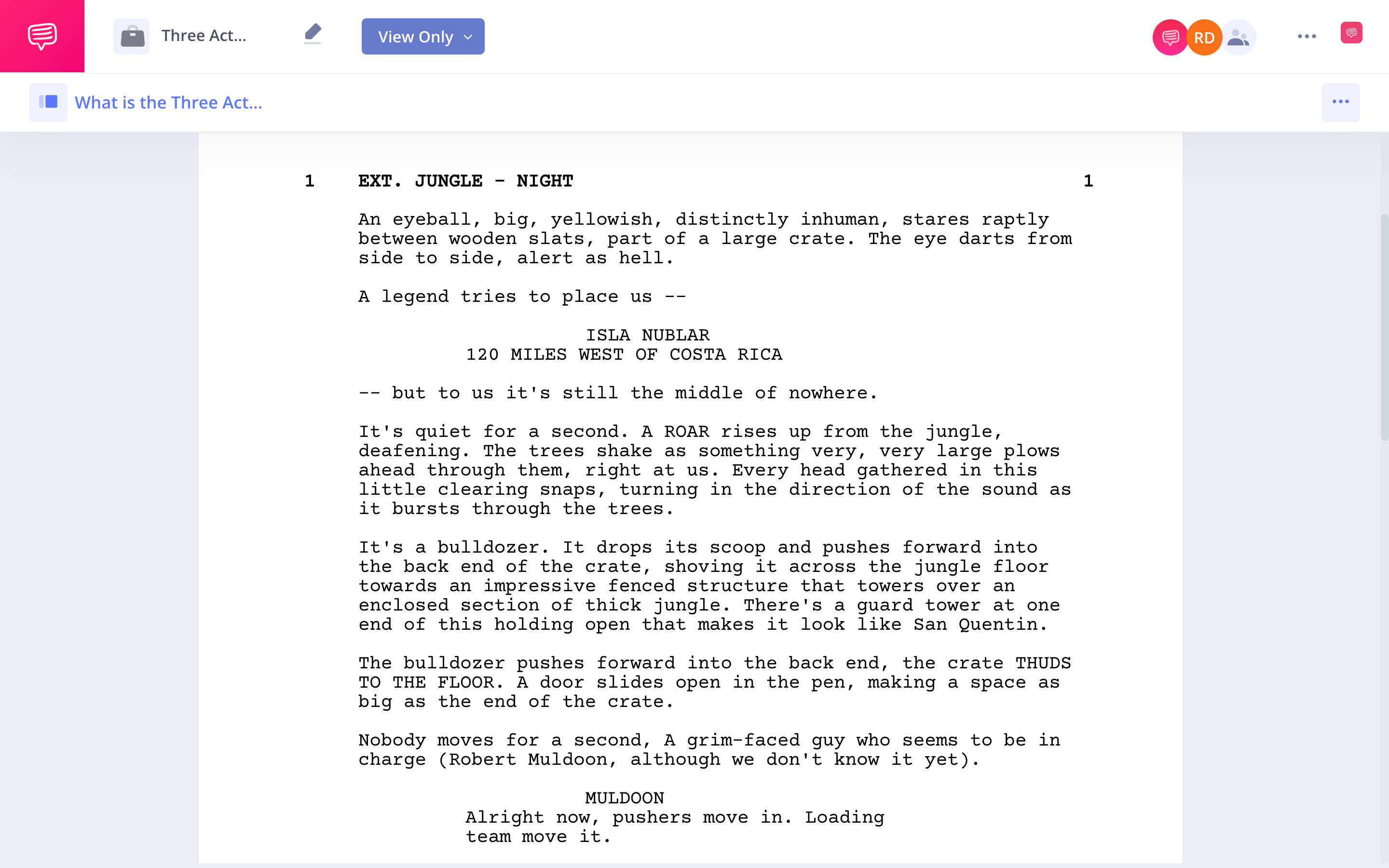

One example of a great movie which closely follows this three-act structure is Jurassic Park. Let’s go through its beats, one by one.

This is the opening of the movie and, in turn, the first act. The main goal here is to captivate the audience. Why should they care? Why should they keep watching?

Jurassic Park piques our interest expertly. Take a look at the alluring first scene in David Koepp’s script:

Steven Spielberg diverged a little from the specifics Koepp lays out, but the core idea is still there: scary, suspenseful, and filled with mystery. As an audience, we want to know where we are, what’s going on, and, by the end of the scene, we really want to see those dinosaurs.

We’ve already gone over what an inciting event does, so let’s jump right into the inciting incident in Jurassic Park– when John Hammond convinces Grant and Sattler to visit the park.

Why is this the inciting event? It gets the plot moving. Our interest has been piqued, and now our protagonists are going right into the belly of the beast.

The first plot point is also commonly referred to as the break into act 2. It’s the point of no return– after the characters cross this barrier, they can’t go back. That’s how this is different from the inciting incident. Sattler and Grant can say no to Hammond and walk away.

This is not so after our first plot point, which is when Alan and Ellie see the dinos in all their glory. Spielberg knows this is a big beat, and thus he uses every trick in his playbook to heighten the awe of the moment:

After the characters see the dinosaurs, there’s no going back. As scientists, they simply have to know more.

The first pinch point happens about a quarter of the way through the second act. This is often the first obstacle, albeit minor, and typically involves the antagonist. Perhaps most importantly, this pinch point sets up the midpoint (more on that later).

In JP, the first pinch point is when Hammond and his team notice that the storm is getting much worse. They recall the Jeeps and Ellie sticks behind, an important moment that affects the structure of the rest of the film.

Of course, this beat also prepares us for the midpoint…

The midpoint is, unsurprising, the halfway mark of the movie. Typically, it is a moment that redirects the plot; a hero thinks they have things figured out when the rug is pulled from under their feet.

Jurassic Park has a very famous midpoint. Again, this is Spielberg we’re talking about: he’s going to make important beats feel important. The reveal of the T. Rex is indelibly imprinted on the mind of anyone who has seen it:

After this, the story has completely shifted. We’ve moved from a narrative of wonder and excitement to one of horror and survival.

Like with the first pinch point, this moment is not as big as, say, the break into act 2 or the midpoint. But it’s important in setting up the third act. Usually, the pinch point is a setback. The protagonist is really in trouble and the audience is starting to wonder how on earth they’ll get out of this.

In Jurassic Park, this is when Nedry dies. This is a huge setback because now the park is very broken, and someone’s going to have to fix it.

Otherwise known as the break into act 3. As such, this plot point segues us into the highest stakes of the story yet.

This is when Ellie turns on the power. It’s a win, but it’s simultaneously a low point for Alan and the kids– Timmy’s almost killed.

This moment also reintroduces the final act’s primary antagonists: the raptors. They kill Arnold and Muldoon, and they’re hungry for more.

The climax is the moment the whole story has been leading up to. It’s the big bang, the final battle, the big kiss.

In Jurassic Park, the climax is when Alan and Ellie are reunited only to be chased down by the velociraptor killing machines. In a moment of deus ex machina, they are saved by the T. Rex. It doesn’t feel cheap, however, because it reinforces the core theme of the film: nature can’t be controlled. This dino food-chain will persist no matter what the humans are doing.

And finally, at long last, the story comes to a close. The resolution is a moment to catch our breath and see how the journey has permanently affected our characters.

The resolution in Jurassic Park shows Alan as a guy who doesn’t hate kids so much after all. The protagonists choppers out of the island, safe and sound.

As Jurassic Park shows us, a story can follow a three-act structure beat-for-beat and never feel boring or unoriginal.

Professional screenwriter and creator of shows like "Community" and "Rick and Morty," Dan Harmon, gives his two cents on how to build a story from the ground up, instead of breaking down what already exists. It still follows a familiar structure but it's another exciting way to approach breaking and developing story.